Teacher training, together with higher education in general, faces the challenge of bridging education and work. Teacher education programmes address this issue by adopting learner-centred and collaborative pedagogical approaches. Such routes include inquiry learning, problem-based learning, and project-based learning, all of which capitalize on authentic professional practice and related phenomena, problems, and situations (e.g., Brush & Saye 2014; Hunt 2015).

Teacher education is also required to bring itself up-to-date by responding to the current digital creation practices, preferences, and cultures of student teachers, as well as their present and future students. Teacher training faces the challenge of bridging education and work. Teacher education programmes address this issue by adopting learner-centred and sociocultural pedagogical approaches. We think that today’s new mobile and blended learning environments create increased opportunities for such processes, including learner-centred approaches, authenticity and dialogical knowledge construction. However, teaching still requires appropriate learning design and structuring.

The setting of our research article was the study module “Networks in Vocational Education” 4 ECTS credit in the Professional Teacher Education programme HAMK, School of Professional Teacher Education. The study module was designed by using the DIANA (Dialogical Authentic Netlearning Activity) pedagogical model, which is seen as one of the learning designing models for existing digital learning environments. The main components of the learning environment provided by the facilitators were an open course blog, containing freely accessible educational resources, and open blogs for the study circles. The module was designed so that each collaborative learning application could be accessed via mobile devices.

Previous studies (Enqvist and Aarnio 2004; Aarnio 2006) have indicated that authentic dialogical learning is difficult in online settings and that the construction of such knowledge should be structured more deeply in the learning processes of teacher education. The DIANA model combines the key factors of learning and teaching in the digital age in an inquiry-oriented practice-based tool and learning framework. At the present time, in many educational settings and systems, becoming a teacher and practising as a teacher require one to work with processes which are, by nature, more communal than ever before: teachers must operate in various learning communities and communities where knowledge is constructed. Dialogical skills are necessary, so that efforts toward authentic, integrative and interdisciplinary knowledge construction can be successful (Aarnio and Enqvist 2016).

The literature on dialogicality in blended and online teacher education and higher education has focused predominantly on dialogical discourse, interaction, and teaching (e.g., Ligorio, Loperfido, and Sansone 2013; Cramp et al. 2015; Sedova, Sedlacek, and Svaricek 2016). However the focus of our study was on authentic and dialogical knowledge construction specifically on the part of the learning community. According to Enqvist and Aarnio (2003), dialogical knowledge construction means that learning is a social process where students, though participation and collaboration, construct a shared understanding. This requires the skills of inquiring and questioning, so that the generation of new ideas and knowledge is possible.

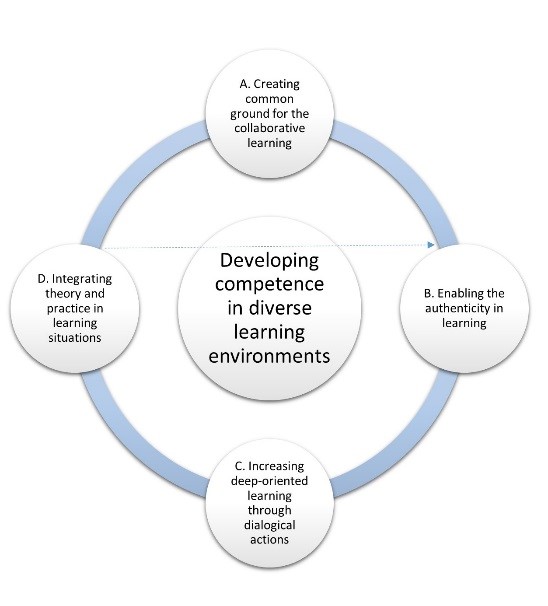

DIANA model in the practice

The revised DIANA model (Fig. 1) starts from cornerstone A, which creates a common ground for learning community. The objective of cornerstone B is to establish authenticity in learning by using problems related to real life and formulating authentic learning questions. These are connected to the learning objectives of the study module. The teacher’s role is to offer scaffolding and guide the students’ learning in the right direction. Deep-oriented learning, through specific dialogical actions and collaborative knowledge construction, is at the heart of cornerstone C. In practice, this entails seeking answers to learning questions set earlier, providing individual contributions, clarifying and questioning the meaning of utterances, continuing the utterances of others and participating in the construction of a shared understanding. Cornerstone D integrates theory with practice and requires the students to weave a collaborative synthesis, create shared artefacts and to search collaboratively for new learning questions pertaining to the learning goals of the study module (Aarnio & Enqvist 2016).

The purpose of our study was to identify the challenges and opportunities inherent in the adoption of the DIANA model and to examine student teachers’ reflections concerning authentic and dialogical knowledge construction. Participants were 63 student teachers (between years 2013-2015) who were following the study module. We used a deductive content analysis to discern relationships between the data and the existing theory. The data for this study was drawn from an online questionnaire and student teachers’ self-reflective accounts.

Key findings

Dialogical problem-solving and knowledge construction in a learning community helped to create a shared and integrated whole through collective understanding. Dialogical approaches and attitudes were regarded by students as factors that deepened the learning process, and learning in study circles was considered to strengthen this tendency. The skills and competences gained by making inquiries were regarded as the most rewarding part of the dialogical actions. Most of the students also felt that they gained new perspectives, thanks to the various skills and pieces of knowledge shared by the participants of the study circle. As one student reported:

‘Through dialogue, one learned to think of the topic from different angles that might never have opened up to one otherwise. The knowledge and experiences of the group helped one realise how to use the content in practice when teaching.’

Our results indicate that deep-oriented learning through dialogical actions was the most challenging part of using the DIANA model (see also Enqvist and Aarnio 2003). As a pedagogical model, DIANA proved to be demanding for students; a problem that is closely connected to a lack of dialogical competence (Aarnio & Enqvist 2016). Although dialogical work is challenging, when done effectively, we believe, it helps learners to create a shared whole through shared understanding. Inquiry skills were shown to be the most important dialogical skills and competences, but listening, reciprocity, and symmetrical participation were also considered key. Therefore, methods that develop dialogical skills and competences should, we suggest, be integrated (e.g., Aarnio 2012) into teacher education as extensively as possible, in order to make collaborative work and problem-solving genuinely dialogical and equal. We agree that the role of teachers is central in promoting a dialogical knowledge construction and learning culture.

This blog post is a short summary of the recently published research article in the Educational Research, entitled “Authentic, dialogical knowledge construction: a blended and mobile teacher education programme”.

Sanna Ruhalahti

Teacher Educator, HAMK School of Professional Teacher Education

Doctoral Candidate, University of Lapland, Centre for Media Pedagogy